Terroir: honest to the bone

Share this story

When dishes are made with passion, you often hear people say that you taste the love in every bite. What you then often fail to realise is that this love is not only expressed during the cooking process. It starts much earlier. Actually, it starts with the earth. The soil that gives life to all the ingredients that chefs use to conjure up top dishes on our plates.

The farmer and his terroir

Terroir feels good in a straightforward setting. It refers to that soil as the breeding ground for the crops grown on it. More than that, it refers to the specific characteristics of that soil that give the crops their individuality. In fact, it even means that you can never grow exactly the same product twice. The soil is at times nutrient-rich and well-watered, at other times challenged and dry.

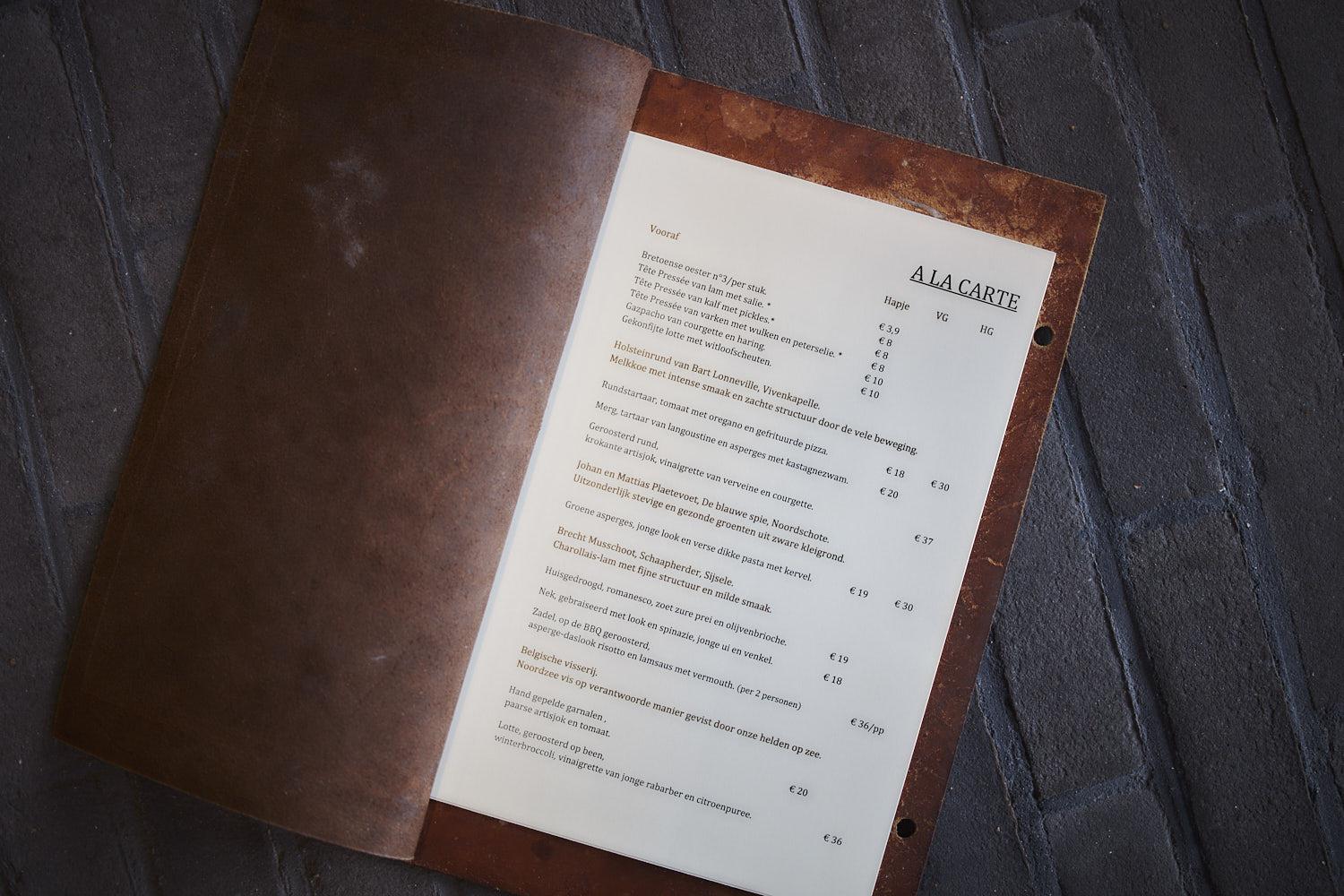

Pieter Lonneville of Atelier Tête Pressée one of the chefs of local soil who shows awareness for the characteristics of 'his' own soil in everything he does. He works with products from local suppliers: unprocessed, artisanal, daily fresh and of the best quality. He calls his gastronomy recognisable, deliciously authentic, a little brutal but honest to the bone.

Terroir is very much also about the individual of the supplier, the farmer himself. How he deals with his soil, the breeding ground for all that grows. How he deals with his terroir. He works within a certain structure and within the values he considers important. Farmers work in and with nature. They anticipate drought and wetness, stormy weather and heat waves, and know that these affect the properties of their terroir.

The masses swing the baton

Pieter Lonneville is a farmer's son and grew up in the Bruges countryside. His father raised cattle specifically for butchers. The pride in craftsmanship and respect for farming can be heard in everything Pieter says about his father, brother and suppliers. It was never his father's ambition to engage in mass production either, but rather to preserve the uniqueness of the product in all its facets.

Defending that individuality every day was and is certainly not the easiest path. Certainly not in a world where mass production and world market prices rule. Moreover, consumer tastes also change. A few decades ago, for instance, nobody wanted to buy beef with fat. However, every healthy cow has a certain percentage of fat. At that time, farmers along the supply side were looking for ways to meet consumer demand.

Mass production of non-fat cattle also became an advantage for butchers. For them, a healthy cow offered a return of 60% meat to live weight. A cow bred for non-fat meat had a 70-75% return . Since butchers in the latter case had more meat and less fat for the same price per kilo, their returns increased to 15%. Healthy fattened animals were so easily wrongly labelled B-quality.

Pieter Lonneville likes to swim against the tide. He introduced the term Holstein in Belgium some 12 years ago. Until then, beef was 'beef'. With a focus on terroir, local production and processing, and healthy high-quality meat, both gentlemen graced the front pages of various newspapers and magazines. Three months later, there was already Holstein in the supermarket, which completely eroded the product and its local anchoring and terroir.

Terroir support

At the end of the 1990s into the early years of the new decade, a lot of chefs kept beef off their menus. Beef offered too few opportunities for pure, authentic dishes. The Fleming's love of a daily piece of beef took its toll on terroir. Terroir in Belgium was seen as non-existent and this was felt in restaurant kitchens.

Chefs then looked to France, where terroir and meat formed a pure combination. Think pigeons from Anjou, lamb from the Pyrenees and veal from Limoges. Terroir thus became something exotic rather than local. Everything had to come from far away. The difference with today is huge.

The only weapon farmers and chefs like Pieter have against all that is mass production is their own portfolio. Making wise, conscious choices and offering them is what makes terroir stronger. There are a lot of great (small) initiatives like North Sea Chefs these days. So consumers are also increasingly getting the value of local produce and terroir. Value that they in turn take into account in their choice of what goes on the plate at each meal.

The Field-to-Fork principle

Chefs like Pieter are fans of the short chain. They buy quality local produce from the farmer. The farmer determines his prices and his supply, there is hardly any packaging material involved and the distance between what grows in the field and ends up on our plates is getting shorter. From field to fork, in other words.

For chefs, this also means a creative exercise. After all, they are cooking with the farmer's fresh supply. Terroir as inspiration. One year the tomatoes are top quality in month X, the following year a cold spring creates a completely different situation.

Also terroir: artisanal rapeseed oil from the Pajottenland region

Twenty years ago, some fields growing rapeseed appeared in the Pajottenland. The initial intention was to grow rapeseed to produce biodiesel. Eventually, the farmer chose to make rapeseed oil for consumption. Rapeseed oil is hugely healthy due to its concentration of omga 3, omega 6 and omega 9.

The taste of rapeseed oil was admittedly not that great. The farmer started looking for ways to improve the taste and discovered that the pellet provided the specific taste of rapeseed oil. He therefore devised a machine to hull the rapeseed. That husked rapeseed was then cold-pressed.

The result was a rapeseed oil that tastes like the terroir of the southern slopes of the Pajottenland region. A surprising combination of hay and cauliflower. Flavours that fit perfectly into Flemish cuisine.

Chef and bacon butcher

To buy animals alive himself, Pieter Lonneville retrained himself as a bacon butcher. If you are not, you buy your meat from wholesalers. The selection of animals is always done in consultation with the farmer. In spring, he talks to the farmer, they discuss the supply and make arrangements around the fattening of his animals. Thus, the lambs featured on the menu at Atelier Tête Pressée are fed and fattened with the leftovers from the production of rapeseed oil (rapeseed bark) from the Pajottenland region. And finally fried in Pieters kitchen in that same oil.

Another advantage Pieter sees in his title of bacon butcher is that he can choose to leave the fat on the meat. A fan of suet, for example, he always leaves it attached to the filet pur to then fry that piece of meat in. This keeps the meat nice and juicy and he also sees the animal's identity much better. In most slaughterhouses, that suet is removed by default. It is seen as waste, not an integral part of a piece of quality meat.

As a bacon butcher, you also learn a lot about animal anatomy. You learn why a certain piece of meat is more tender than others. How to dry meat. Which cuts are fragile and how to keep the fibre structure intact. By talking to the farmer, by trusting his expertise and also tapping into his own knowledge, every piece of meat that comes out of Pieter's kitchen retains its individuality.

Terroir: simplicity adorns

Terroir is not doing what your neighbour does. It forces you to look at your own background. It is not about copying what someone else is doing successfully. It is being yourself, finding yourself, making mistakes and learning from your mistakes. Small-scale and often simple.

Terroir also requires an open mind. It asks you to be aware of what happens around you and not just listen to who shouts the loudest. Above all, it is also about respecting the supplier and loving his products. If you open yourself up to listen to farmers and see the qualities of the products they offer, you put yourself and authentic dishes on the map. And no matter how you spin it, you taste that. In every bite.